On Saints, Sacrifice, and a Poet Who Might Have Started All This.

Every year around this time, everything turns pink.

Suddenly we are all supposed to feel something specific. Romantic. Hopeful. Coupled. Desired. Or at least convincingly unbothered.

And yet, when you look at the origins of Valentine’s Day, it’s… strange.

Before roses and heart-shaped boxes of chocolate that somehow all taste the same, mid-February in ancient Rome meant Lupercalia — a fertility festival involving ritual sacrifice and pairing by lottery. Not exactly soft lighting and handwritten notes. It was physical. Earthy. A little chaotic.

Then Christianity layered itself on top of it. Several Saint Valentines, possibly more than one martyr. Stories blurred. Legends stitched. A priest defying an emperor. A letter signed “from your Valentine.”

It’s hard to separate fact from folklore.

Which feels oddly appropriate.

And then, unexpectedly, comes poetry.

In the 14th century, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote “Parlement of Foules.” In it, birds gather on Saint Valentine’s Day to choose their mates. Whether he meant February 14th specifically is debated. But something shifted there.

Love became literary.

It became courtly. Intentional. Romanticized.

We sometimes act like Valentine’s Day is timeless and sacred, but it’s actually layered — pagan ritual, Christian martyrdom, medieval imagination, Victorian sentimentality, and modern marketing all stitched together.

A patchwork.

And maybe that’s the point.

Love itself is layered. Rarely pure. Rarely simple. Often inherited in forms we didn’t consciously choose.

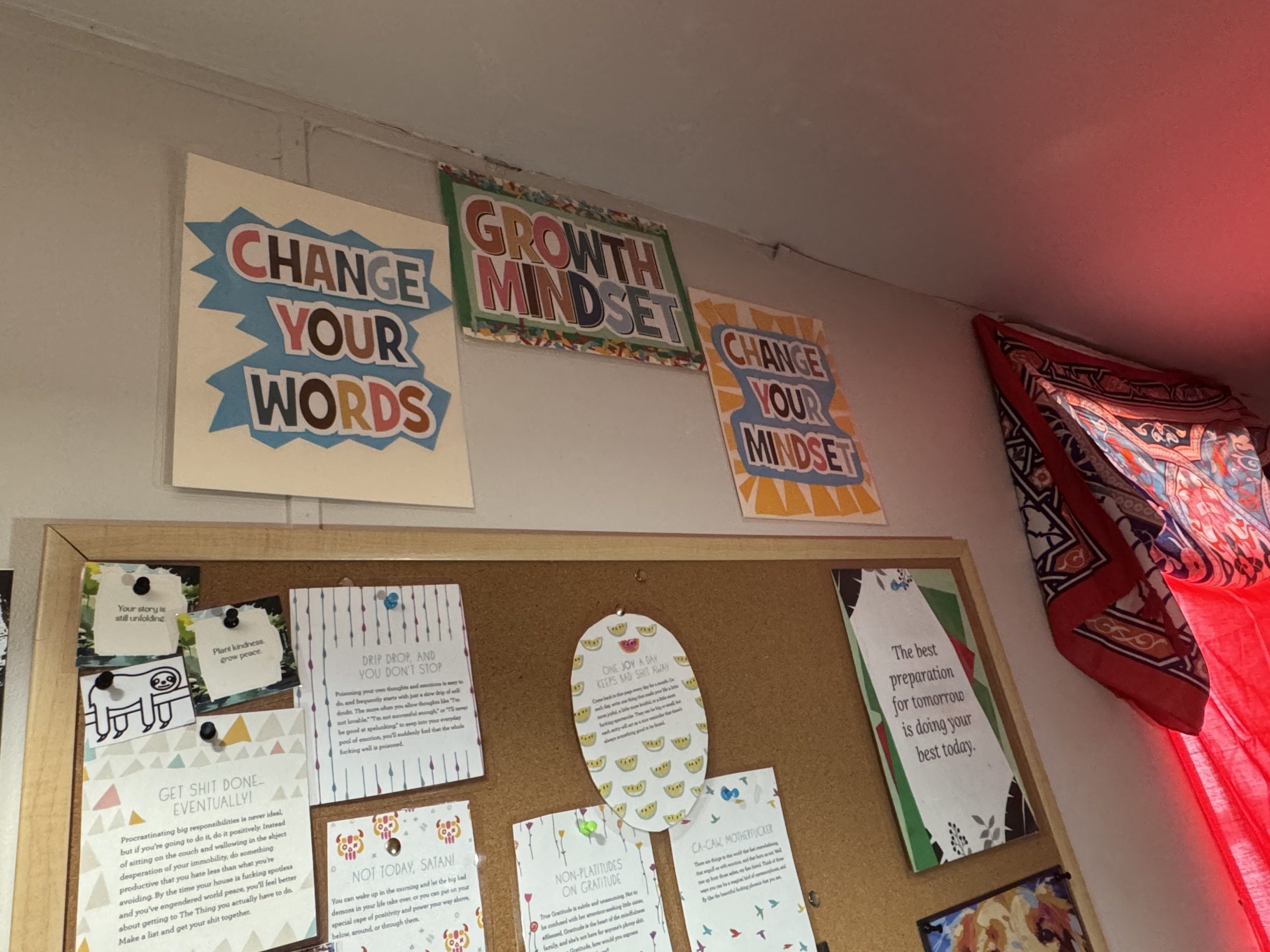

We grow up absorbing ideas about romance from poems, holidays, movies, expectations. We participate in rituals we didn’t invent. We measure ourselves against traditions that were, in many ways, improvised.

It’s a little ironic.

A holiday rooted in sacrifice and myth now asking us to perform perfection.

And yet.

Somewhere inside all of it, something real still exists.

Two people choosing each other.

Or one person choosing themselves.

To “dare to mend” on Valentine’s Day is not to reject it entirely. It’s to see it clearly. To acknowledge the absurdity without becoming cynical. To recognize that love has always been complicated, layered, human.

Chaucer imagined birds gathering under divine order to find their mate.

Today, we scroll.

Different medium. Same longing.

The question hasn’t changed much over the centuries:

Who am I choosing?

Why am I choosing them?

Am I choosing from fear, pressure, tradition — or from wholeness?

Maybe this is the quieter work of February 14th.

Not the performance.

The reflection.

Not the urgency.

The discernment.

Not the need to prove love exists.

But the willingness to define it intentionally.

Valentine’s Day was never as simple as the cards suggest. And neither are we.

So perhaps the most honest way to honor it is not with grand gestures — but with clarity.

To mend what has been broken.

To unlearn what was inherited without question.

To choose love — if and when we do — with open eyes.

That feels braver to me than roses.

That feels like progress.

That feels like daring.